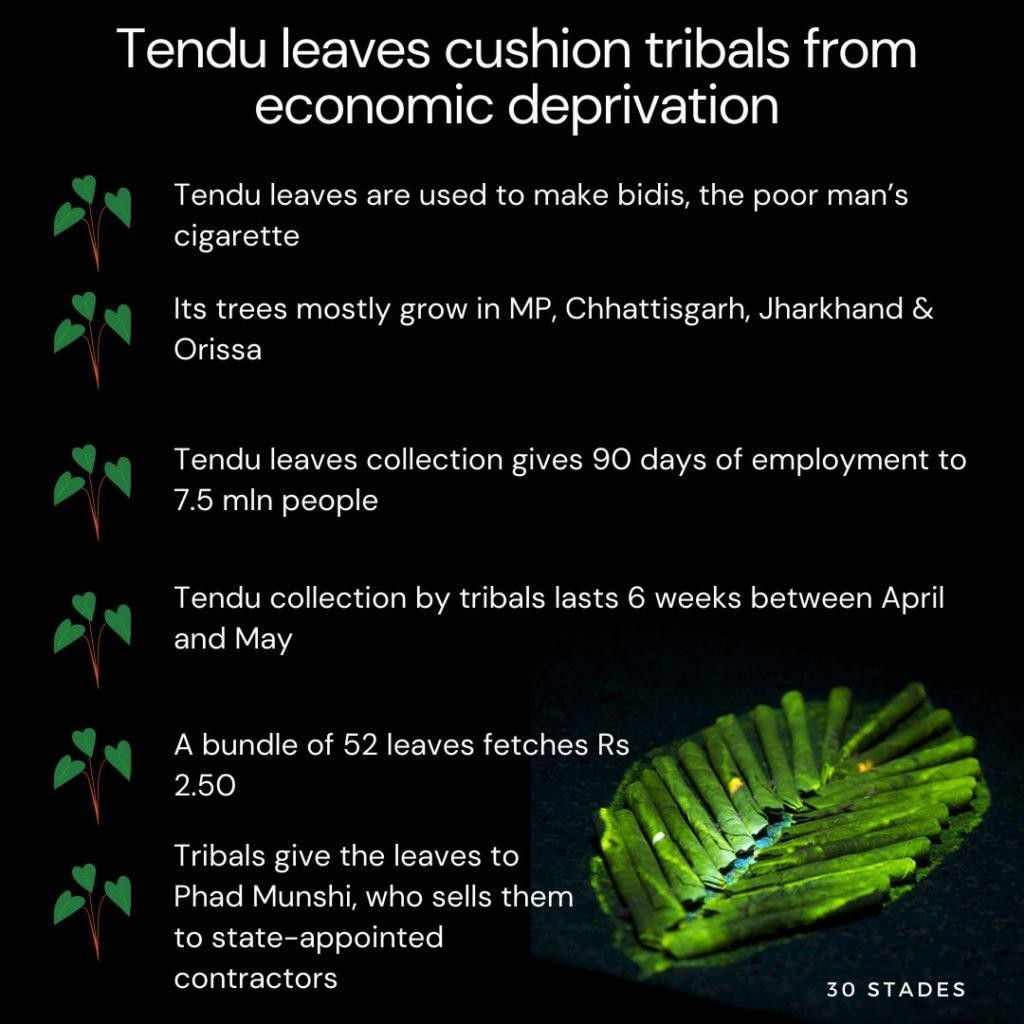

Tendu leaves cushion tribals from economic deprivation during COVID-19

- At around 4 am, Shamli Devi leaves her home with a water bottle, torch and a clean cloth, walking nearly 5 km to the nearest forest in eastern Madhya Pradesh’s Mandla district. For the next five or six hours, Shamli toils away in the heat, plucking leaves from tendu trees. She carefully collects them in the piece of cloth to avoid breakage because these leaves will be used to wrap tobacco flakes and tied with a cotton thread to make bidis, the poor man’s cigarette.

- For generations, the tribal population of eastern Madhya Pradesh has been dependent on tendu leaf collection for their livelihood. The collection season between April and May coincided with the Coronavirus outbreak this year. And, at a time when the country was reeling under COVID-19, tendu leaf collection provided a cushion to the tribals, helping them mitigate the economic impact of lockdown and provide financial support to families.

- “We revere nature but now, we are doubly thankful. This time, the money from tendu collection has given us a lot of financial support. We were almost running out of cash soon after the lockdown was imposed (March 25). With the money I got from tendu leaves, I was able to buy provisions for my family and also materials for next season’s farming,” she says.

- At a time when most economic activity has come to a halt, the continuation of tendu leaves collection due to the absence of COVID-19 in deep forests underscores the importance of sustainable living .

- Its collection is mostly practiced in the tribal dominated pockets of western and eastern Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa, and parts of west Bengal, Bihar and eastern Maharashtra. Madhya Pradesh is the biggest contributor, bringing in nearly 25 percent of the national tendu collection.

- Shamli, who lives in Sudgaon village, has been collecting tendu since she was a teenager.

- After collecting the tendu leaves, she sorts them at home into batches of 52 leaves. “For each batch we get Rs 2.50. With my experienced hands, I can make 150 to 200 batches each day, says Shamli.

- The batches are taken to a collector, locally called Phad Munshi, who further sells it to contractors assigned by the state. Tendu leaves and bamboo make up around 60 percent of the total minor forest produce (MFP) trade in the country. Trade of both of these is monopolized by state governments.

- The government procures them through its agencies such as the forest department, Tribal Development Cooperative Corporation, and State Forest Development Corporations to ensure there is no exploitation by middlemen.

- When the tendu collection season is over, she and her husband undertake farming over their 2 acre land on which they grow mainly wheat.

A blessing in tough times

- She has four daughters, three of whom she has managed to send to schools outside the village, the youngest one goes to a local school.

- While tendu leaf collection is a crucial economic activity for rural households in the summer season, this time it has been more so because the lockdown has hit poor people hard, leaving them without jobs and income.

- “Depending on the number of people from a family involved in tendu collection, a family is able to earn Rs 5000-15,000 on an average per season,” says Sumendra Punia, team coordinator from Pradan, a civil society organisation working for tribal empowerment.

- “It is a sure shot activity that happens just before the onset of kharif season and gives cash support to these families,” says Punia

- Older family members sort tendu leaves while younger ones go for collection. Pic: Pradan

- “This year it was more gainful as there wasn’t much work under MGNREGA to the lockdown and the safety measures that were put in place. Panchayats struggled to open up work, which required less labour so that social distancing could be maintained,” he says.

- NTFP include fruits and nuts, vegetables, fish and game, medicinal plants, resins, essences and a range of barks and fibres and a host of other palms and grasses.

- “If they work in MGNREGA, then the payments are delayed, wages are low and they have to work for the full day in the summer heat,” says Punia.

- In contrast, they can decide the time of work while collecting forest produce, mostly avoiding the peak heat hours of the day.

- Anita Vishwakarma of Dupta village in Mandla says the money from tendu leaf collection has helped. “My husband is a mason and he could not find any work during the lockdown,” says the 28-year-old.

- A packet with 20 bidis can cost anywhere between Rs 5 and 20

- Along with her mother-in-law, she earned Rs 9,000 this time. “We could buy all essential supplies and stationery items and clothes for my two children. Otherwise we were facing a cash crunch,” she says.

A sustainable way of life

- Tribal communities have a traditional relationship with forest based produce as it provides them livelihood and food security. “Around 220 million people depend on forest for their livelihood and they have been practising sustainable living,” says Richard Mahapatra, managing editor of Down to Earth magazine.

- The real challenge, Mahapatra says, is for those in the formal economy and the cities to change their lifestyles. “We have to give up our over- consumption and resource-intensive lifestyle,” he adds.

- Around 92 percent of the workforce is in the informal sector and they have suffered the most in the COVID pandemic as they are vulnerable to economic shocks. “The role of the government post COVID should be more pronounced in public health, food security and sustainable employment for the marginalised sections,” he says.

- Over the past two decades, governments, development agencies and non-government organisations have encouraged the marketing and sale of NTFPs as a way of boosting income for poor people and encouraging forest conservation.