How a German Vet’s Love for Camels is Saving a Unique Community in Rajasthan

- The camel is part of the landscape of Rajasthan; the icon of the desert state, part of its cultural identity, and an economically important animal for nomadic desert communities like the Raikas, who have been herding camels for centuries. Renowned as the only camel herders and breeders in the world who also protected them from slaughter, the Raikas’ knowledge about all aspects of the camel’s behaviour, breeding and health care is legendary.

- The existence of Rajasthan’s nomadic Raika tribe revolves around a legend that inextricably ties the fate of the camel and the community together. The Raikas believe that the camel was created by Lord Shiva at the behest of his consort Parvati. Parvati shaped a strange five-legged animal from clay and asked Shiva to blow life into it. At first he refused,saying that the misshapen animal would not fare well in the world, but later, he gave in. He folded the animal’s fifth leg over its back giving it a hump, and commanded it to get up by saying “Uth“. And that is how the camel got its Hindi name. The animal then needed someone to look after it, so Shiva rolled off a bit of skin and dust from his arm and fashioned out of this the first Raika.

- This is why the Raikas take their responsibility as custodians of camels very seriously. They have also developed “akal- dhakal”, a unique collection of different languages and sounds to communicate with their camels. What is also unique is the the musical folklore surrounding camels that date back to over 700 years. The Raikas are also among the last people to shear designs on the camels’ sides – this is possible only because of the deep trust between a herder and his animal. The Raikas bond deeply with their camels. Photo Source Sadly, camels and their herders who were once the pride of the desert state, are now struggling to survive. Their traditional way of life and cultural identity has been usurped by disappearing grazing lands, mechanized farming, parasitic disease, and decimated demand for camels. The Raikas also find themselves struggling to survive in the face of disdain for, and often active hostility towards, their migratory traditions.

- In Rajasthan, the number of Raika herders have dropped from about a million in the 1990s to about 200,000 today. As for camels, the numbers have fallen so drastically in the past 30 years that it has prompted the Rajasthan government to declare it as their state animal in 2014, hoping to increase protection for the animal.

- Ilse Köhler-Rollefson, a German veterinarian who arrived in Rajasthan in 1990 for her PhD, has dedicated her life to the camels and the camel people of Rajasthan. In her book Camel Karma, she chronicles her life’s passion, and how her research subject changed the course of her life. After experimenting with several ideas to revive the unique camel culture of the region, Köhler-Rollefson set up an NGO called the Lokhit Pashu-Palak Sansthan in Pali, Rajasthan that serves as an advocacy group for the Raikas and their camels.

- “It’s not just about the camel as such. It’s about preserving for the future a unique and caring human-animal relationship that exists between the local Raika camel-herding community and the animal. It can serve as a model for a responsible relationship with farm animals, when industrial livestock keeping is expanding,” she tells The Better India.

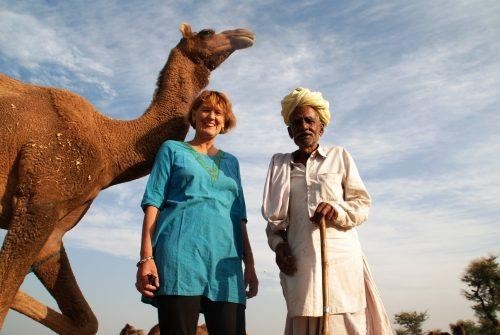

- Ilse Köhler-Rollefson with a Raika and his camel. Photo Source Trained as a veterinary surgeon, Köhler- Rollefson was drawn to camels after encountering herders in Jordan. A PhD research fellowship to study camel socio- economics and management systems brought her to remote Raika settlements in Rajasthan.

- Köhler-Rollefson was enchanted by the intimate and affectionate relationship between the camels and the Raika families.

- However, she also realised that due to a larger change in desert ecology and the pastoralist way of life, the Raikas, who once kept camels in their hundreds, are now finding it difficult to manage even a few.

- Shocked and moved, she decided to take up their cause.

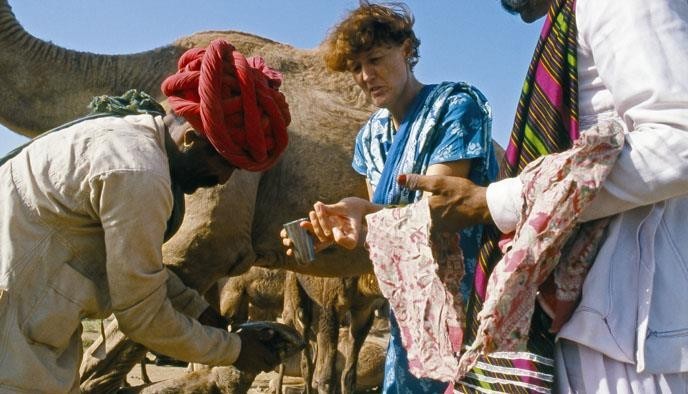

- It wasn’t easy for Köhler-Rollefson, an outsider, to become an activist and advocate on behalf a community that has traditionally been wary of outsiders. Ultimately, it was her veterinary training that made the Raikas first take note of her. Diseases were killing camels and many had miscarriages. So, Köhler- Rollefson began helping the herders treat sick camels. She also began organizing medicines for the animals only to realise that most companies had stopped manufacturing them.

- That’s when she recognised the need for steady funding to help the Raika and their camels. So, in 1996, she set up Lokhit Pashu- Palak Sansthan (LPPS) at Sadri with her associate Hanwant Singh to sustain the

- community’s livelihood as well as their animals. Today, the LPPS helps the Raikas by providing camel veterinary care using both traditional remedies and modern medicine.

- “We’ve reached a point where even state and national government officials seek our advice,” says Köhler-Rollefson, who has earned the local moniker “Our Lady of the Camels.” Ilse Köhler-Rollefson helping Raikas treat their sick camels. Photo Source Under the aegis of LPPS, Köhler-Rollefson has also organized camel yatras to spread awareness among local communities across Rajasthan about what’s happening to their iconic animal. LPPS also organizes the Marwar Camel Culture Festival, a modest three-day event held at Sadri that features bazaars to promote camel milk and wool products, evenings livened by Raika and Langa music, visits to a Raika village, discussions on the future of camel rearing, and even a camel-milking competition.

- In 2010, Köhler-Rollefson set up Camel Charisma, a micro-dairy near Jaisalmer that produces about 150 liters of camel milk a week. Her goal is to perfect supply and management, eventually boosting production to 300 liters a day. While raw milk can be consumed locally, shipments must be pasteurized, refrigerated, and frozen for transport to Delhi and elsewhere in the region.

- Explaining the reason behind the dire need to preserve the camel with help of a dairy she says, “The camel is the state animal of Rajasthan for one and the identity of Rajasthan is interlinked with the camel. Secondly, considering climate change with widespread water scarcity and annually rising temperatures, how can we ignore the camel? It is the dairy animal of the future. In all other countries, the camel population is increasing, only India is losing it. That is a very dangerous situation if we lose such an asset,” she says

- Camel Milk. Photo Source

- Camel’s milk is noted for its purported health benefits due to the varied diet of camels— the tree leaves and shrubs they eat as a part of

- their diet are known for their medicinal properties. Low in fat, it is good for diabetics and for the lactose-intolerant. Its ability to lower blood sugar levels in Type 2 diabetes patients is scientifically proven, as is its impact on autistic children who are reported to sleep better after taking relatively small amounts of camel milk.Camel Charisma also makes products such as scented soap (from camel milk), scarves and dhurries (from camel hair) and handmade paper (from camel poo). Recently, with help from Danish cheesemaker Anne Bruntse, Camel Charisma has come out with unique varieties of camel cheese that are available at the brand’s Camel Café, where visitors can also drink camelccino and camel chai.

- Since its inception, the organisation has created a network of about a thousand active camel breeders.

- Most of them are uneducated, but we are happy to see that young people are becoming more active and taking initiatives to market camel milk. They all face three issues: disappearance of grazing areas, lack of disease control, and lack of market for camel products. We have been addressing all three issues. Most importantly we have developed a range of innovative camel products,”she says.

- The Camel Charisma store. Photo Source LPPS also fights for the restoration of grazing rights of the Raikas. In 2004, a Supreme Court judgement made it difficult for the Raikas to take their camels into Kumbhalgarh sanctuary for grazing. If the Raikas went into the sanctuary, as they had for generations, they risked being fined or arrested by the forest department.However, this stand of the forest department has been challenged by experts. Camel grazing in Kumbhalgarh sanctuary can hardly cause harm to the forest, says Anil K. Chhangani, a scientist who has studied the problem closely. He explains that camels are primarily browsers and not grazers. Soft-hooved and gentle to the soil surface, camels also play an important role in the regeneration of a number of trees.

- Chhangani’s three year study with an American researcher, Paul Robbins of the University of Arizona, used satellite images of the sanctuary between 1986 and 1999 to establish that human interference in the forest actually led to greater diversity in floral coverage in Kumbhalgarh where the Raikas used to take their cattle for grazing.

- The study also suggests that reviving the traditional grazing lands like gauchars (village pastures), orans (village forests), parats (wastelands), and agoris (catchment areas of ponds and rainwater harvesting

- structures), can help resolve the Kumbhalgarh issue. However, the problem is that these village commons have been taken away and diverted either to industry or for putting up solar and wind energy farms. The desert is no longer deserted; there are several contenders now for space. The loser is the gentle giant of this ecosystem – the camel.

- As can be seen, most of the time, blanket policies miss the nuances of the realities of communities of the Raikas, even though they are the ones who best understand the fragile balance of their ecosystem. LPPS’s consistent efforts to rectify this have finally yielded results.

- Photo Source In October 2016, the government of Rajasthan announced a string of measures to protect the camel and camel herders. Under the ‘Ushtra Vikas Yojana’ (Camel Development Plan), the government will now provide a Rs 10,000 cash incentive to camel herders on the birth of each calf. Also, medical camps will be set up for camels suffering from ‘surra‘, a dangerous disease which infects its blood and often proves fatal. Local training centres will be set up for herders to teach them how to handle the animals profitably by utilising camel products such as hair and milk.

- The very fabric of the Raika community is tied to its animals. This makes it crucial to ensure that conservation of the camel goes hand-in-hand with the conservation of nature, with the creation of sustainable livelihoods being an important part of the plan. As Köhler-Rollefson says, the future of Rajasthan’s camels and their traditional herders now lies in its milk!