Nidhi Dugar Kundalia’s White as Milk and Rice chronicles lives of India’s isolated tribes battling identity conflict

- In her book White as Milk and Rice: Stories of India’s Isolated Tribes, author Nidhi Dugar Kundalia records the ways of life of six tribes in modern-day India, as they navigate a hyper-globalised world, dealing with issues of identity and access to resources.

- In his 1968 documentary Close to Nature, Shyam Benegal recorded the way of life of the Bastar tribes, and explained how the 20th century tribal welfare schemes were enriching their communities. There were schools and other educational institutions to make them aware of the mainstream society around them, besides providing them with access to a doctor and healthcare services, a cooperative store for basic utilities, free milk- booths, and more. “In spite of this, can the tribals prevent civilisation from overrunning them?” Benegal asks in the documentary, further inquiring if they can “prevent a commercial exploiter or the overzealous reformer”, through the film’s voiceover. “Unfortunately for the tribals, change means loss of identity, a break from their past,” he adds. While the threat of a cultural, religious, and social reconstruction loomed large, their traditional lifestyle remained largely unchanged.

- Today, five decades later, as Nidhi Dugar Kundalia records the life of Birsu, a woman of Bastar’s Maria tribe in her book White as Milk and Rice: Stories of India’s Isolated Tribes, it is clear that their entire way of life has been radically altered. Birsu’s everyday concerns include worrying about the miners of giant corporations getting closer in order to destroy their jungles, with the police being rendered powerless against these companies. She notices how the fireflies have disappeared and how the mahua trees die young because of increasing storms. However, what most strongly reflects the changes that have engulfed them is Birsu’s internal conflict about whether her daughter Radha will grow up in a ghotul (a traditional hut commonly constructed by the Gond and Maria tribes) like she did, or go to a school. She finally decides on the latter, as she reasons in the book: “She may then become a police officer, or teacher…or even a Mao”. Bastar. All photos courtesy Nidhi Dugar Kundalia, except where indicated otherwise.

- This shift in daily life is something that most tribal populations in the country are experiencing in varying degrees. Faced with the challenge of adapting to a rapidly developing country amid breathless globalisation, they are increasingly encouraged to integrate with mainstream society. Through deforestation and mining, their land and resources are ruthlessly encroached upon, destroying the way of life that they are familiar with. For some, this integration with society is also understood as a type of colonisation, as sometimes tribal children are enrolled into ‘factory schools’, where they are given a mainstream education. They are, however, often ill- treated, and made to feel disconnected from, and ashamed of, their own culture.

- Kundalia writes in her book: “Over the last few decades, rapid urbanisation has affected the character of their lives; the loss of their innocence and the damage to their environment are, perhaps, inevitable.

- ” Through a focus on the human element, the writer brings to the fore the impact of development and the resulting conflict of identity among the population. “What’s going on in their head? How are they negotiating their life with all the changes happening? What are they going through on a human level? I was interested in exploring all these things,” she says. “While they were trying to understand all these changes, they themselves changed a lot, without them realising,” she adds.

- “On the one hand, they want their forest life and culture to be untouched, and want not to be questioned about certain practices…On the other hand, they want to explore the world of mainstream society that has opened up to them, and have access to education, healthcare, and equal job opportunity,” the writer, who’s also a journalist, explains.

- This ongoing change is also reflected in the songs of the Halakki women from the Ankola district of Karnataka, another tribe that Kundalia documents in her book. From singing about a group of women journeying on a boat, to commentating on the nature of mothers-in-law and praising the abundance of the Sahyadri forest, they now also sing of rich landlords who are offered paans when they visit. As a result of development and legislation, the Halakki men lost the two major sources of livelihood they depended on

- — hunting and agriculture. They took to working as daily wage labourers by day, while alternatively indulging in alcoholism.

- A few Halakki women have come together to agitate against unlicensed liquor shops along the northern coast of Karnataka, which have encouraged their men into becoming useless alcoholics, leaving the women to fend for themselves. Among them is Padma Shri Sukri Bomma Gouda, also known as the ‘singing woman of Ankola’, who has witnessed first- hand the changing ways of her tribe, as chronicled by Nidhi Dugar Kundalia.

- Besides the Marias of Bastar and the Halakkis of Ankola, White as Milk and Rice also presents stories of individuals from across four other tribes, always focusing on the transition and uncertainty surrounding them. These include the Kanjars of Chambal, the Kurumbas of the Nilgiris, the Khasis of Shillong, and the Konyaks of Nagaland.

- While aware of her non-tribal background, Kundalia’s process included attentive listening, meticulous research, and minimal author intervention. Her goal was to record their stories the way they wanted them to be told, offering the tribes a platform through which they could claim their narrative to a certain extent. The book also takes readers into the minds and settlements of said indigenous people, — instead of reporting as an outsider — offering a visual, emotional, and balanced view of their lives.

- While some tribes still live deep within forests and are untouched by the society beyond, Kundalia chose to focus on those tribes that are on the brink of change. While putting the book together, she faced challenges like finding a trustworthy translator and getting her subjects to open up and communicate with her, besides overcoming geographical hurdles. Most of them, she recalls, “were very hard to crack.”

- “It did take a long, long time. They don’t know what I need. They don’t understand all of this,” she says. Sometimes, they simply didn’t mention things because of how obvious that knowledge seemed. At other times, “the person could be lying or not giving you enough (information) because she or he is not sure about how you will project the issue,” she says.

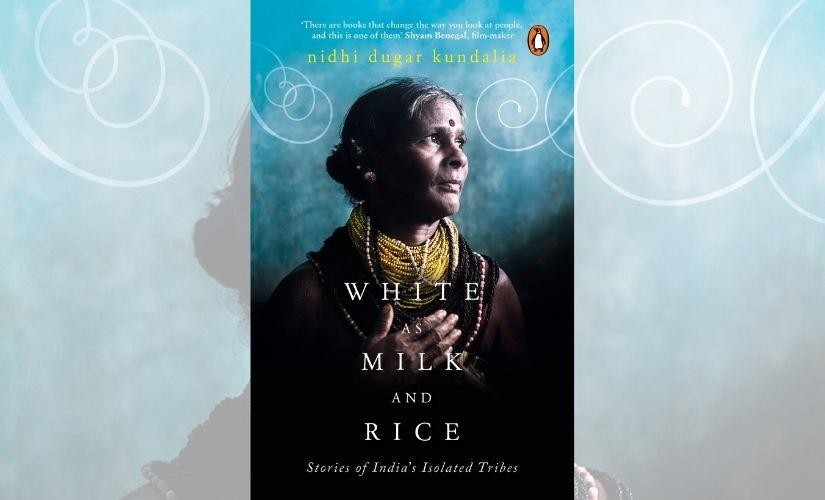

- White as Milk and Rice: Stories of India’s Isolated Tribes by Nidhi Dugar Kundalia book cover. Photo courtesy Penguin Random House India.

- This distrust stems from having experienced centuries of exploitation, making them wary of outsiders. The Kurumbas, for instance, claim to harbour a lot of information about traditional medicine. “They say they have cures for diseases like AIDS, but they’re not willing to share it because they aren’t sure what we’ll do with that information and how the tribe will be exploited,” the author says.

- Most Konyaks today have converted to Christianity as a consequence of the British instilling a deep sense of shame in their identity during their reign. “They are

- desperate to prove that they are normal, that they do not belong to the tribals at all. As far as possible, they avoid their native identity,” says Kundalia.

- The question about tribal conflict of identity, finally, has no simple answer. “I’ve written a book exploring that and still, I’ve not found the right answer,” she says. The most important thing that can be done in this regard is to hear and respect the tribal voice. Most importantly, while it’s still too early to say if India’s tribal culture will be completely wiped out, or estimate the extent to which it will change, it is true that a lot of it is being lost to irresponsible development.

- However moving forward, how much of their culture is to be preserved should be entirely up to them. “All I ask for is to let them make that choice. Let them decide what they want to be. There should be legislation where they get to choose whether they want to educate themselves or not, whether they want forest land to be encroached upon or not,” the author concludes.